|

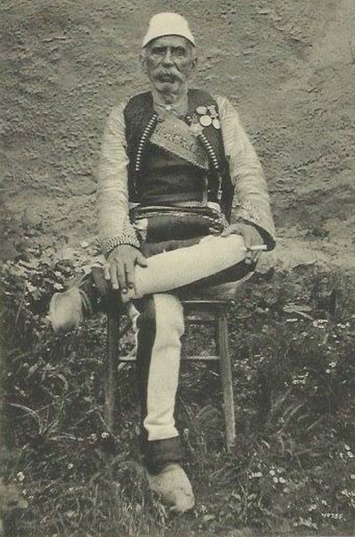

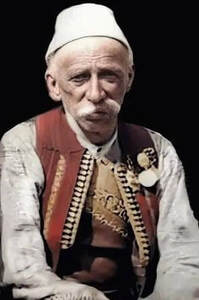

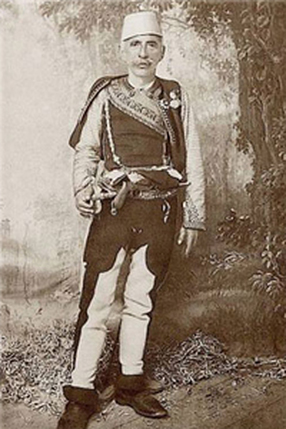

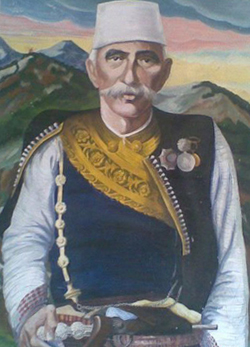

THE PEOPLE'S HERO - THE LIFE AND DEEDS OF DEDË GJO’ LULI, THE VALIANT MAN OF THE ALBANIAN MOUNTAINS

The highland uprising of 1911, a fierce and bloody war that lasted for four months in the mountains, had a 71-year-old military leader named Dedë Gjo’ Luli of Traboini - Hoti. The figure of this noble man, mountaineer, and patriot, is mentioned in history and is well known and honored among our people. Dedë Gjo’ Luli is the personification of the Albanian mountains, as that word is understood in terms of organizing for self-defense, and in a military and customary sense. The Albanian mountains, as centers of resistance against foreign invaders, are highly valued by many well-known historians of Europe. The German professor Dr. Ferdinand Huepe writes: “Only in the Albanian mountains was the Slavic fury turned back.” The Frenchman Ciprion Robert emphasized, “the Highlands are the main nerve of Albania,” while Dora d’Istria would affirm, “in the northern Highlands the spirit of independence has found shelter.” There is no doubt that the Albanian mountains and the Highlands have played a very important role in the history of the Albanian nation, but our written history has not emphasized this role much, nor in the way that it should have. The Ottoman occupation continued for an entire century, from the first battles near Gjirokaster in 1380 until the fall of Shkodra in 1479. |

|

During this period in Albania, self-defensive neighborly (not tribal) communities were created, called mountains, which the distinguished historians Hamilton Gibb and Harry Bowen have called “strong resistance centers in Albania.” Among these mountains, Hoti has been mentioned as early as 1416, the mountain of Tomadhe in 1459, the mountain of Bena in 1469, followed later by others as well.

In this environment, on the mountain of Hoti - a center of resistance, which not by chance is known to the people as the first mountain - Dedë Gjo’ Luli was born, grew up, and reached manhood. There he learned the meaning of the fundamental national duties, such as the defense of the Hoti Mountain and the fight for freedom and self-rule of Albania. Dedë Gjo’ Luli learned that in those mountains the Skenderbegian spirit of liberty had never faded. Deda himself testifies to this. In the letter which he sent to the Shkodra archbishop on 02/27/1904, among other things, he said: “If there are any Albanian priests of our blood and brotherhood, I swear by the sweat and the blood which Skenderbeg shed for Albania, to step forward and help us.” The efforts and the blood of Skenderbeg, these for Deda were the greatest oath! The symbol of liberty and independence of the Albanian people, the national Hero, Gjergj Kastrioti was for him more precious and more sacred that any other thing. That the Skenderbegian spirit of liberty and self-rule was embodied in the mind of Deda, we see this in his subsequent demands. When asked at a meeting with the Turkish consul in Cetina, whether they wanted “the Red Book” for themselves or for all of Albania, Deda answers “first for ourselves and later for all of Albania!” Deda clearly knew what he was fighting for, and this is expressed beautifully in this folksong:

Dedë Gjo’ Luli writes a letter: To send to Shkodra’s Pasha, That Albania doesn’t want anything else, Except to govern its own people! Observing Deda as a military man, it can be stated without doubt that he was the equal of educated European generals, and much better than the Turkish generals. As a military man and general of distinguished abilities in the organization and mobilization fields, as well as in commanding, in the masterful exploitation of the tactical and operational features of rough mountainous terrain, Deda stands out as no one else. Having acquired these qualities, in the years 1879-1880, we see Deda as Commander of the forces of the highlands and general Vice-Commander in the South, where the Commander was Preng Bib Doda, while Hodo Sokoli was commander in the city of Shkodra and its surroundings. Deda had extraordinary ability in using religious sentiment to better serve the national cause. After spending some time in the trenches, the mountaineer warriors asked to go to church for mass. No, responded Deda. The priest will come to the trenches and hold mass. In this way, we do not abandon our duties and still have mass. By drawing to himself the striking forces, other territories could now initiate uprisings more easily. Berat and Vlora were ready, but somebody with the code name 333 was stopping them. How can this be shown concretely? Very easily. During the first days of March, the people of Mirdita attacked Turkish garrisons in Orosh and Kashnjet. The commander of the 24th Division deployed in Shkodra evaluated the situation as very dangerous. To face the attacks in Mirdita, he withdrew four infantry battalions from Tuz and, adding some other ones from Shkodra, sent all of them urgently to Mirdita under the command of Chief of Staffs Colonel Pertef Beu. From Prizren, as well, an infantry detachment, accompanied by mountain artillery, was sent to Mirdita. Knowing that the Tuzi garrison was reduced in number significantly and that a surprise attack would be a sure success, Deda sent Nik Gjelosh Luli and his son, Kola, to begin the attack. So, on March 24, the post of Rapsha was attacked and taken. |

|

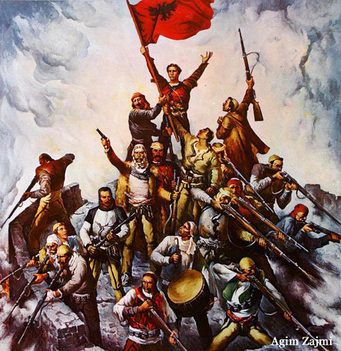

On March 25, the posts in Stare, Pikale, and Selishta were taken, while Kelmendi broke into the church and took the weapons, which were gathered there in 1910. On March 27 they attacked and took some positions around Deçiç, while Kelmendi seized the two posts of Vermoshi. On the same day, 500 soldiers, four cannons, and 1000 Shkodran volunteers left Shkodra and headed for Koplik-Kastrati, but were stopped for three days at the Përrua i Thatë (The Dry Creek), by the Kastrati forces waiting for Dodë Preçi. On March 28 Tuzi was attacked, and, on the next day, fell into the hands of the insurgents. So a free zone from Tuz to Drin was created, leaving into the hands of the Turks only Shipçaniku and Deçiç. On March 30 the Turks initiated a counterattack toward Deçiç, but suffered losses, and won nothing. On March 31, during the night, Pertef Beu, using a deceptive plan, was able to withdraw his entire army from Mirdita without losses and entered Shkodra. On April 1-2, the mountaineers celebrated Easter and did not post guards, which allowed the Turkish forces to go from Përroi i Thatë to Deçiç, and from there to Shipçaniku. On April 3, Dedë Gjo’ Luli went to Qafa e Kishës and took command of the insurgent forces. On April 6 he directed the attack against Deçiç, expelled the Turkish garrison and raised the Albanian flag! On the same day in Kalivare of Mirdita, an assembly of twelve bajraks (“bajrak” is a territorial unit created by the Ottomans as an administrative and military entity) appointed Preng Marka Prenga as general commander of the insurgent forces of Mirdita. On April 10, Turkish forces, comprising 34 batalione këmbësorë (infantry batalions), twenty heavy machine guns and twenty-four mountain cannons, under the command of Turgut Pasha, arrived in Shëngjin. Now both sides were making preparations: the Turks for a general offensive, while the mountaineers for active resistance. Turgut Pasha in Tuz placed eleven thousand infantry, eight heavy machine guns, and eight mountain cannons in combat formation with the object: 1. Prevent the mountaineers from going to Montenegro 2. Invade Deçiç 3. March toward Rapsha |

|

In Koplik, he stationed eleven thousand infantry, four heavy machine guns and eight mountain cannons:

1. To block help from Dukagjini on the right flank 2. To invade Kastrati and Shkreli 3. To wind up in Rapsha. From the North, Etem Pasha began by lining up five thousand infantry, eight heavy machine guns and twelve mountain cannons against the mountaineers. This force comprised twenty-seven thousand soldiers, twenty heavy machine guns, and twenty-eight mountain cannons. Against this force Deda positioned 380 Grudjan (from Gruda), 900 Hotjan (from Hoti), 100 Diaspora, 500 Kastratas and Shkrelas (from Kastrati and Shkreli), 500 Shaljan in the south, and 900 Kelmendas in the North, making a total of 3280 people. The ratio with regard to combat forces alone, excluding armaments, was 8 to 1 in favor of the Turks! Besides, Turgut Pasha was trained in Turkey and Germany, while Dedë Gjo’ Luli and the other chieftains were “educated” only in their own mountains. Turgut Pasha planned a “scorched earth” campaign and declared that he “would teach a lesson to the Albanians, that they would not forget for seven generations.” After many local probing battles, the offensive of Turgut began on a large scale in May. But he did not achieve the results he expected. At first the heavy cannons had an effect on the mountaineers who had never fought against them before, but soon after they got used to them! The progress of the Turkish army was very slow. For this reason, on May 25, Turgut strengthened his first line of offense to the tune of forty thousand infantry, forty heavy machine guns and sixty cannons. All of these against five thousand one hundred mountaineers! But despite this army, the Turkish forces on May 27 had managed to reach only the line of Arrëz, hillocks, and Razem, so they had advanced no more than 3-6 km, while in the North they had arrived at Selca! This was the active tactical defense of Deda. While, in the political field, efforts were made by the Turks to subjugate them, and the mountaineers on their part were trying to gain as many rights as they could, the Turkish command was somewhat in chaos. On July 7, led by Dedë Gjo’ Luli, the mountaineers unexpectedly attacked Deçiç and expelled the terrified Turks. Seeing this retreat and unusual disorder, supposedly to stop the flight in panic, the Turkish commander ordered his own artillery to open fire on the soldiers who were running as quickly as they could. A beautiful scene! Behind their backs the mountaineers were shooting at them with rifles, in fact with the rifles that they were throwing to the ground as they fled, while in front of them their own commander, Turgut Pasha, was waiting for them with cannons. With this action Turgut Pasha disgraced himself before the world! After the scandalous event of July 11, the Sublime Porte released him from duty and removed him from Albania. This general, who called himself “triumphant joy,” could not accomplish the plan that he drafted with so much fanfare, but suffered defeat in the battlefield at the hands of the mountaineers led by Dedë Gjo’Luli. This is the work written in blood in the mountains of Albania that Dedë Gjo’ Luli has left us! The duty of students of Military Science is to reveal - through a detailed analysis of the course of military operations - these brilliant pages in the history of traditional Albanian Military Science, where Dedë Gjo’ Luli rightly occupies a rank of the first order. Concerning the interruption of the military operations of this uprising, different appraisals have been made, some of which are wrong. The History of Albania incorrectly states: “The resistance of the mountaineers was broken, finally, by the clan leaders, who, faced with the difficult situation which was created in the first part of August, agreed to sign the agreement with the Turks, based on Istanbul’s proposal!” First, it should be said that the resistance of the mountaineers was not broken. Second, it was not the mountaineers, but the Turks who wanted to stop the fighting on any condition, because if the rains were to start and after them the snow, the Turkish army would have suffered irreparable damage! |

|

If the Turkish army were in the Highlands during the winter, everything would be in the mountaineers’ favor! Lastly, it is known that to calm down the mountaineers, Ismail Qemali and Jak Serreqi went to Montenegro. They personally advised the mountaineers to stop the uprising. Regarding this, a year later, in July of the year 1912, in a letter that Ismail Qemali sent to Abdi Toptani, he admitted that in the previous year they had made a mistake, so he made a self-criticism. During a life full of efforts to benefit Albania, Deda had a very clear and precise political position: he was Albanian. I will give a few examples. Shkodra in 1913 came under the administration of an International Commission. At a meeting organized in front of the building of the Prefecture of Shkodra, the English Admiral Cecil Burney said to Deda: “Hoti and Gruda are finished.” Deda fired back: “You sir, can sell your garden if you like; but mine, I do not sell it, nor do I give it away.” The Admiral changed the subject and started to “advise” the men of Hoti and Gruda to keep quiet; otherwise they would forcefully send them back to their birthplace, which that the Conference of the Ambassadors had granted to Montenegro. Deda replied: “Does Europe have the right and the force to stop me from shedding my blood?” On the occasion of the departure of the International Commission from Shkodra, Ismail Qemali contacted Deda and asked of him unity, order, and moderation. Deda sent him this telegram: |

“The Great Highlands, in the course of ordering its affairs, now and in the future, with wisdom and in accord with the canons of the country, will be a powerful and faithful tool in planning and bringing order to the governing center of the entire Nation!” I think the above answer expresses Deda’s opinion quite clearly.

As a participant at the Convocation of the Albanian League of Prizren in 1878, the Convocation of the League of Peja in 1899, and in different inter-regional Assemblies and meetings between the Highlands and the city of Shkodra, Deda met many patriots. However, in terms of the way their lives unfolded, he resembles Themistokli Gërmenji in many ways: both were unyielding patriots, both were never tempted by foreign money, both fought for national freedom, both martyrs of the Homeland, and both had the same tragic end.

In the pantheon of the Albanian nation, Dedë Gjo’ Luli deserves a place of honor. He should be known. In order for him to be known, many books should be in circulation regarding the life and deeds of this unyielding man of the Albanian Mountains, this living sword of Albania.

As a participant at the Convocation of the Albanian League of Prizren in 1878, the Convocation of the League of Peja in 1899, and in different inter-regional Assemblies and meetings between the Highlands and the city of Shkodra, Deda met many patriots. However, in terms of the way their lives unfolded, he resembles Themistokli Gërmenji in many ways: both were unyielding patriots, both were never tempted by foreign money, both fought for national freedom, both martyrs of the Homeland, and both had the same tragic end.

In the pantheon of the Albanian nation, Dedë Gjo’ Luli deserves a place of honor. He should be known. In order for him to be known, many books should be in circulation regarding the life and deeds of this unyielding man of the Albanian Mountains, this living sword of Albania.

By: Pal Doçi

(Fordham U. Symposium, 85th anniversary of the Great Highland Uprising, April 13, 1996)

(Fordham U. Symposium, 85th anniversary of the Great Highland Uprising, April 13, 1996)

|

DEDË GJO’ LULI, ONE OF THE DISTINGUISHED HEROES OF THE ALBANIAN NATION

Time, with its continuous flow, in many cases covers with the dust of neglect even those events, which in their time echoed powerfully, and as a result, even the names of the protagonists of those events. Unfortunately the end result of such a phenomenon has been that many important events in the unwritten history of the Albanian people have been covered by the dust of neglect, owing to the historic circumstances in which our grandparents and forefathers had to live, or more correctly, to survive. As a consequence, today we have a limited knowledge, not only of the ancient periods, but also of the relatively new times in the history of our people, one of the most ancient people in the Balkans. For example, we do not know much about our ancestors’ unyielding resistance to the assimilating efforts of the different invaders, Romans, Slavs, Turks, etc. But the fact that the Albanian ethnic stock has been able to survive and to preserve its identity, testifies clearly that our forefathers and ancestors preserved as their greatest treasure, their language and traditions, which they inherited generation after generation, and along with these; the determination, as well, to be free and independent in their motherland. Precisely for this reason, they fought with courage, even in very poor conditions, against enemies who were far more numerous and much better armed, sacrificing even their lives for freedom and independence. It is sufficient to remember that eve after the death of our National Hero, Gjergj Kastriot Skenderbeg, when Albania came under the rule of the Ottoman Turks, the Albanians always remained unconquered citizens, and time after time rebelled against their invaders. Many of those uprisings have been covered with the dust of neglect, because unfortunately historical circumstances did not permit our ancestors to perpetuate them, even in the form of brief notes. In spite of that, some of these uprisings have not remained unwritten. It is sufficient to remember here the unequal wars of the Kelmendi mountaineers against the Turks in the XVII century. One of these events is mentioned by Bogdan in his famous work Çeta e Profetëve (1685), Pj. I, Lecture IV, paragraph 15, where he says: |

“Can anyone deny that Vuça Pasha who, in order to raise an army of twelve thousand people, his millions in gold were not enough, was poorer than our men of Kelmendi, who gathered nearly five hundred people, with only one call: “Come those who are brave” and killed Vuça Pasha, in the year of our Christ 1639. Out of necessity they ate the bark of an oak tree, like the best part of the flour; yet still this food tasted much better to them than lamb or veal to the Pashallares (high government officials during the Ottoman Empire).”

I mentioned this historical event of the XVII century, not only to point out the insurgent and freedom-loving soul of our mountaineers, but also to emphasize that such historic events, transmitted from mouth to mouth and from generation to generation, have served as a “school” for the formation and strengthening of that which can be called the Albanian “national conscience.”

This conscience became ever stronger during the centuries of Turkish rule, and assumed pan-Albanian dimensions in the second half of the XIX century and the beginning of the XX century.

From this point of view, the Great Highlands Uprising of the year 1911, directed with so much wisdom, courage and bravery by Dedë Gjo’ Luli, was not something accidental, but a continuance of the constant efforts of our mountaineers and all of the Albanian people to live free in their homeland, which they inherited generation to generation from their ancestors.

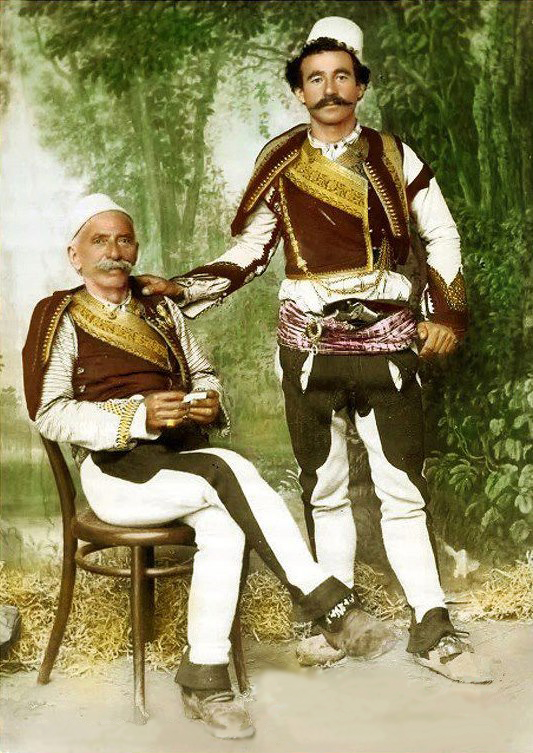

Dedë Gjo’ Luli and his brave mountaineers were taught this feeling of love for freedom in the “school” of popular tradition, where they learned, among other things, to preserve the language and customs of their ancestors, and to be ready to sacrifice their lives for the freedom of their homeland, and that, in pursuit of that goal, they should not fear any threat, but fight on with courage against their enemies, using the arms which they would grab from them.

The expression that “history repeats itself,” in this case, is not without foundation.

I mentioned this historical event of the XVII century, not only to point out the insurgent and freedom-loving soul of our mountaineers, but also to emphasize that such historic events, transmitted from mouth to mouth and from generation to generation, have served as a “school” for the formation and strengthening of that which can be called the Albanian “national conscience.”

This conscience became ever stronger during the centuries of Turkish rule, and assumed pan-Albanian dimensions in the second half of the XIX century and the beginning of the XX century.

From this point of view, the Great Highlands Uprising of the year 1911, directed with so much wisdom, courage and bravery by Dedë Gjo’ Luli, was not something accidental, but a continuance of the constant efforts of our mountaineers and all of the Albanian people to live free in their homeland, which they inherited generation to generation from their ancestors.

Dedë Gjo’ Luli and his brave mountaineers were taught this feeling of love for freedom in the “school” of popular tradition, where they learned, among other things, to preserve the language and customs of their ancestors, and to be ready to sacrifice their lives for the freedom of their homeland, and that, in pursuit of that goal, they should not fear any threat, but fight on with courage against their enemies, using the arms which they would grab from them.

The expression that “history repeats itself,” in this case, is not without foundation.

As in the earlier uprisings, Dedë Gjo’ Luli and his warriors of the Great Highlands, even though small in number, unarmed, without sufficient clothing and hungry, by fighting with courage and using only the arms that they had seized from the enemy, forced the notorious Turkish general, Shefqet Turgut Pasha to return home with shame, leaving in the battlefield a large number of dead and wounded soldiers and others that became captives.

So, the unschooled commander, Dedë Gjo’ Luli, with his brave mountaineers, also unschooled, unarmed and hungry, defeated a general who had been schooled in the best military academies of the time, along with his army that was armed to the teeth.

But Dedë Gjo’ Luli was not only a “born” commander, but also a determined activist of the national cause of Albania. His participation in the Lidhja e Prizrenit (League of Prizren) in 1878, the Greça Meeting of Elders in June of 1911, and his constant interest in the fate of Albania during the critical period of 1911 and 1912, are testimony of this fact.

That is why, during the visit of our Hero in Vlora after the proclamation of Independence in 1912, Ismail Qemali correctly referred to him as “a loaded rifle for Albania.”

But the unequal war of the Albanian people for freedom and independence, of course, had its innumerable victims.

One of those was Dedë Gjo’ Luli, the Hero of the Great Highlands and of the entire Albanian nation, who was treacherously killed in 1915, and along with him, his family, too, was wiped out.

But Dedë Gjo’ Luli always remains alive as a symbol of the Albanian Man, who for the sake of the homeland sacrificed his life and his family.

By: Prof. Shaban Demiraj

Head of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Albania

(Fordham U. Symposium, 85th anniversary of the Great Highland Uprising, April 13, 1996)

Head of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Albania

(Fordham U. Symposium, 85th anniversary of the Great Highland Uprising, April 13, 1996)